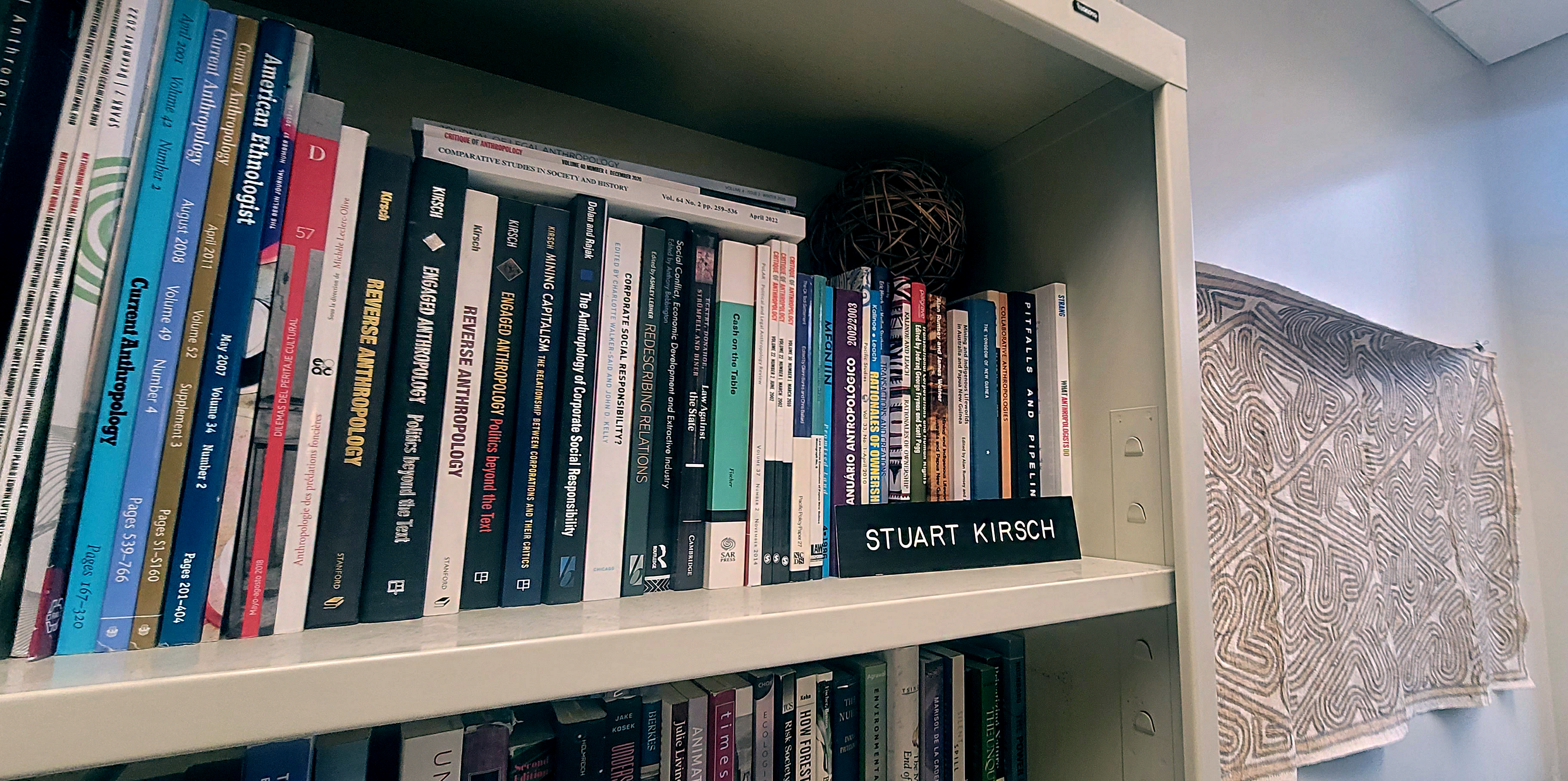

FACULTY – Roy A. Rappaport Collegiate Professor of Anthropology

I’m an environmental anthropologist, [though I wasn’t always one]. At the beginning of my career, I worked in Papua New Guinea with a group of people who lived downstream from a large copper and gold mine that was slowly destroying their environment. And, over time, I became involved in their struggle against the mining company. They ended up taking the owners of the mine to court in Australia, and I worked with the lawyers, and the indigenous communities that were affected by pollution from the mine. And from there, unexpectedly, I became what’s called an engaged anthropologist, and I’ve spent most of my career working with indigenous communities, fighting to protect their land rights, and also fighting to reduce or repair environmental impacts on their land. This work eventually led me to a position [where] I could focus on both academic and engaged research at the University of Michigan.

[As an engaged anthropologist], for most of my career, I’ve worked extensively with people outside the academy…with indigenous leaders, with lawyers, and also more recently with engineers. [Working with them], I started to learn about what‘s called design thinking, or the anthropology of design, as a general way of reorienting my work so that it has practical value. It’s not something a lot of anthropologists do, although I think it’s starting to gain momentum. Instead of just communicating our findings to other anthropologists and our students, actually take the practical knowledge that we have gained, and use it to help others design better, whether it’s responses to climate change, or responses to mining or social problems, collaborating with people outside of the academy to make the world a better place.

Since the early days of my career, I’ve also been thinking about the scale and scope of these kinds of problems which often require me to work in lots of different places, especially my current focus work on climate change which isn’t in any one place, but rather is an example of something I’ve taken to calling everywhere research. [For example,] one of the topics I’ve been learning about for my current research project on the postcarbon transition is the dynamics of innovation in the production of cement and concrete, which [contributes] about 8% of all global greenhouse gas emissions. And so I studied industry in northern California, which is environmentally progressive, a little bit in Michigan, which tends to be more conservative, and also in Bucharest, Romania, to gain an understanding of how things work in the European Union. I also audited an engineering course on materials [at the University of Michigan] taught by Professor Victor Li. It’s not enough to work in any one place. You need to be mobile to see the bigger picture.

After my work on mining, I realized that [climate change] was the next problem I wanted to focus on. If I’m an environmental anthropologist, I should go after the great white whale. I should try to tackle the most important problem in my field, right? And one of the things I noticed and lamented was that anthropologists studying climate change…have focused primarily on its consequences, important to study, yes, valuable to know, yes, and also [provides] a strong rationale for changing things. But for the most part, anthropologists have shied away from looking at the causes of these problems. And so that struck a chord with me as someone who studied mining as a cause of environmental problems, alongside the experiences of people living downstream. And so I wanted to shift attention to the causes of climate change and encourage other anthropologists to shift their focus as well. [The] anthropologist Laura Nader, in the early 70s, coined the phrase ‘studying up’ to look at corporate power, state power, and military power, not just to understand their consequences, but also to look at how those systems of power work to reinforce each other and end up reproducing the problem. So I wanted to bring the approach that I had taken in my earlier work on mining to bear on climate change even though it’s something of an unusual space for anthropologists. Most of the people I interview are a bit puzzled at first, asking me: ’What does an anthropologist have to bring to this conversation?’ It’s a space dominated by natural scientists, physicists, economists, and policymakers. The answer that I give them is anthropologists can help by providing a bigger picture of how this all works, right? By studying up.“

Being an anthropologist also means I think not just in centuries or millennia, but in terms of the much longer history of the human species. And I understand that we’ve gone through many different transitions before, from the development of food production, to urbanism, to global capitalism, the Industrial Revolution, and now we’re facing climate change. And while we used to think in terms of the outdated idea of carrying capacity, that an island or a country could only support or sustain so many people, time after time, we’ve broken through those barriers, with technological innovation. So I have no doubt that we can develop the technical capacity to address these problems. It used to be that people would say that we just need the political will to do so. Now, in Europe, at least, people tell me that it’s really a matter of financialization, as conservative as that may sound. Because we need the economic structures in place to pay for the necessary technological changes. Ultimately, a solar panel on my roof will pay for itself, right? But the question is, and let me put it really directly, it’ll pay for itself, but it won’t necessarily pay more than money in a bank that’s earning interest. So how can we rethink our economic perspectives to address a problem that’s existential and global in scope and urgent, instead of just focusing on this narrow sense of profit?

A lot of my other colleagues [who have been] thinking about these issues, [they] want to abolish capitalism, or promote degrowth, which is generally only attractive to people in the Global North who already have enough, etc., and these ideas are worth debating. There’s a lot that can and should be done to change the way we currently do things.

But several years ago, the famous journalist, Naomi Klein, wrote her book ‘This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate.’ Her main thesis was that we have to do everything completely different, [but] I just don’t see the potential for human society to change everything everywhere all at once, and given the urgency of the climate crisis, we can’t afford to wait for that to happen. And regrettably, I don’t believe in the power of revolutions anymore. Because I’ve seen too many of them fail. The same people stay in power. You know, you’re not increasing power sharing, you’re not gaining more economic justice. So I want to address the urgent challenge of climate change but not necessarily try to solve all the problems of the world at the same time.

I’m teaching two undergraduate classes right now and there’s a conversation we’ve been having in the Department of Anthropology around the curriculum that I’m trying to address. A lot of disciplines orient their teaching around reproducing their field of study. So anthropologists, for instance, teach people how to become anthropologists. But what I recognize is that most of my students, while great and smart, will probably not end up becoming anthropologists. Instead [they] will work in a bank or a corporation or start a business or become a lawyer or work in the food service industry, open their own restaurant, or whatever else they might do. So, what does anthropology have to offer them? What advice do I have to share with them? And what I’m preaching is that everyone has a role to play in addressing climate change. So, if you do work in a restaurant, you could look at food waste, you can look for ways to reduce what gets thrown away, you can work to develop vegan options, right? Because you know, meat and dairy consumption has a huge impact on the climate, equivalent to the impact of coal in energy systems. If you work in a bank, or on Wall Street, you could come up with financial instruments that promote or encourage people to install solar and drive EVs and make your money back. I mean, banks make a lot of money, helping Americans take mortgages out to buy a house, why can’t they do something similar around green energy? If you’re a lawyer, maybe you can sue some of the mining companies that destroy the environment, or help the state design policies that are environmentally friendly. All of my students are interested in environmental issues. And they’re not going to be anthropologists, necessarily, but they are going to be in occupations where they can have an influence, right? If they just keep this in the forefront of their mind.“

As part of the LSA Year of Sustainability, LSA Dean’s Fellow Cherish Dean sat down with a range of students, staff, and faculty across the University to illustrate the various relationships people across campus already have to this work, to showcase ways people can get involved, and to highlight the reasons that this work should matter.

For personal reasons, Stuart Kirsch’s profile will not contain an abbreviated transcript.

Cherish can be reached at [email protected]. To contact the LSA Year of Sustainability Team as a whole, please contact [email protected] .